In Corona March, I went to the bakery, to the supermarket, around the square, and took photographs.

ON MARCH 8th I TOOK A TRAIN FROM MANNHEIM back to my apartment in Berlin. The occasion of my trip was a reading I gave at the Ernst Bloch Center in my hometown of Ludwigshafen. As it turned out, my reading was one of the last readings during these Corona times. The manager had called me in advance and asked if I still wanted to keep the date or if I wished to postpone. I got the call just before arriving.

The atmosphere in the room foreshadowed what was ahead: few people were in attendance. Shortly after all events were canceled one after the other, at first only the big ones like the book fair in Leipzig, then also the smaller ones. By that time, most people had given up making plans. To avoid contagion, people no longer shook hands. The Chancellor had made an appearance to announce the new situation, but the restaurants and cafes remained open without any restrictions. Nobody on the buses and trains respected the rule to touch surfaces as little as possible or to avoid them altogether. Now, just three weeks have passed, but it seems to me that I am writing about another era.

I quickly decided to jump on a train that was going to Berlin. It was not very busy, and I sensed we were following the same path as the virus from the moment I got on board, though I didn’t foresee the route that the train would take. It was extremely slow, traveling via the Niebelungen city of Worms and the city of Bingen, to Bonn, Cologne, Düsseldorf. I was a little queasy because I was in the part of Germany that was the worst hit by the pandemic, which was not yet called that but already was that. The train continued leisurely onward to the cities of the Ruhr area, finally Lower Saxony to Wolfsburg, and at last to Berlin. I got on the S-Bahn, from there I changed to Alexanderplatz and to the U5. Since then I’ve only been in Friedrichshain, my neighborhood, and I see public transportation only from the outside: passing by, sometimes empty, or with very few riders.

Other countries imposed strict curfews, and on March 22nd Germany moved to implement a softened form of quarantine, with contact restrictions and the closing of most shops. Public life has largely come to a standstill. I may leave my apartment for shopping or to get air, but everyone is to avoid contact and activities that are not absolutely necessary.

Health Minister Spahn spoke of the “calm before the storm”: there are still comparatively few Corona deaths in Germany, and the capacities of the clinics are still somewhat reassuring, but the increase of those infected leaves much for people to fear in the coming weeks. Every day brings bad news in excess, from Italy, Spain, France, now also from the USA and probably also from Great Britain. The economy is under greater threat now than it has been since the war. Never in my life has the future been as obsolete as it is right now, because every day the situation changes, and everything to come is uncertain and unpredictable. “Open,” said the Chancellor.

Plans for the coming months don’t make sense. For June 1st I have an airline ticket to Istanbul and then four months based at the Tarabya Cultural Academy to explore the city and Turkish culture. But at the moment I am not allowed to enter there and I am fine with that for now. However, what will become of the cultural sector in a global economic crisis? What will we live on?

Here in my apartment and in the streets around it, the nightlife district around Simon-Dach-Straße is oppressively quiet. Halligalli is over. There are no tourists anymore, and we can’t fly away to escape the situation, either. Everywhere I find a surprising seriousness and deliberateness. How bad will it be? Will we come out of our relatively impressive comfort zone with just a few scratches? Or will the world after Corona become another world, completely different?

The next few weeks will reveal much about which path is more likely. And what to do as a writer? I’m writing daily, but it’s notes of the day, notes of what the media brings. No One Knows Anymore is the title of a novel by Rolf Dieter Brinkmann, who is 80 years old these days. Sometimes I like the forced test of will of staying here in the apartment, with the calm, the books, the seriousness. But mostly I’m depressed by the limitations, the lack of green, blue, yellow, fresh air, space, and the touch of the people who love me. Even the flower shop on Niederbarnimstraße had to close.

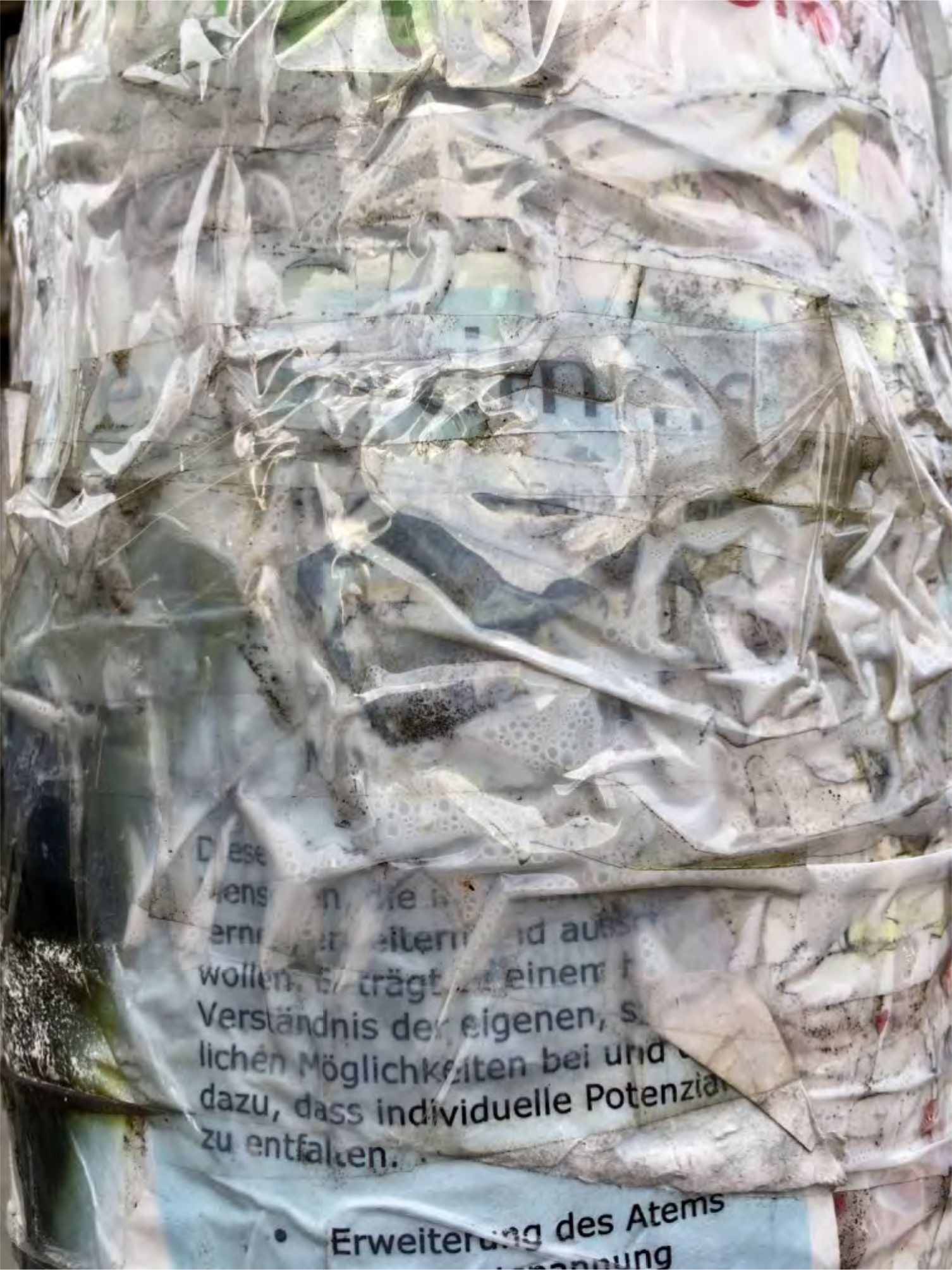

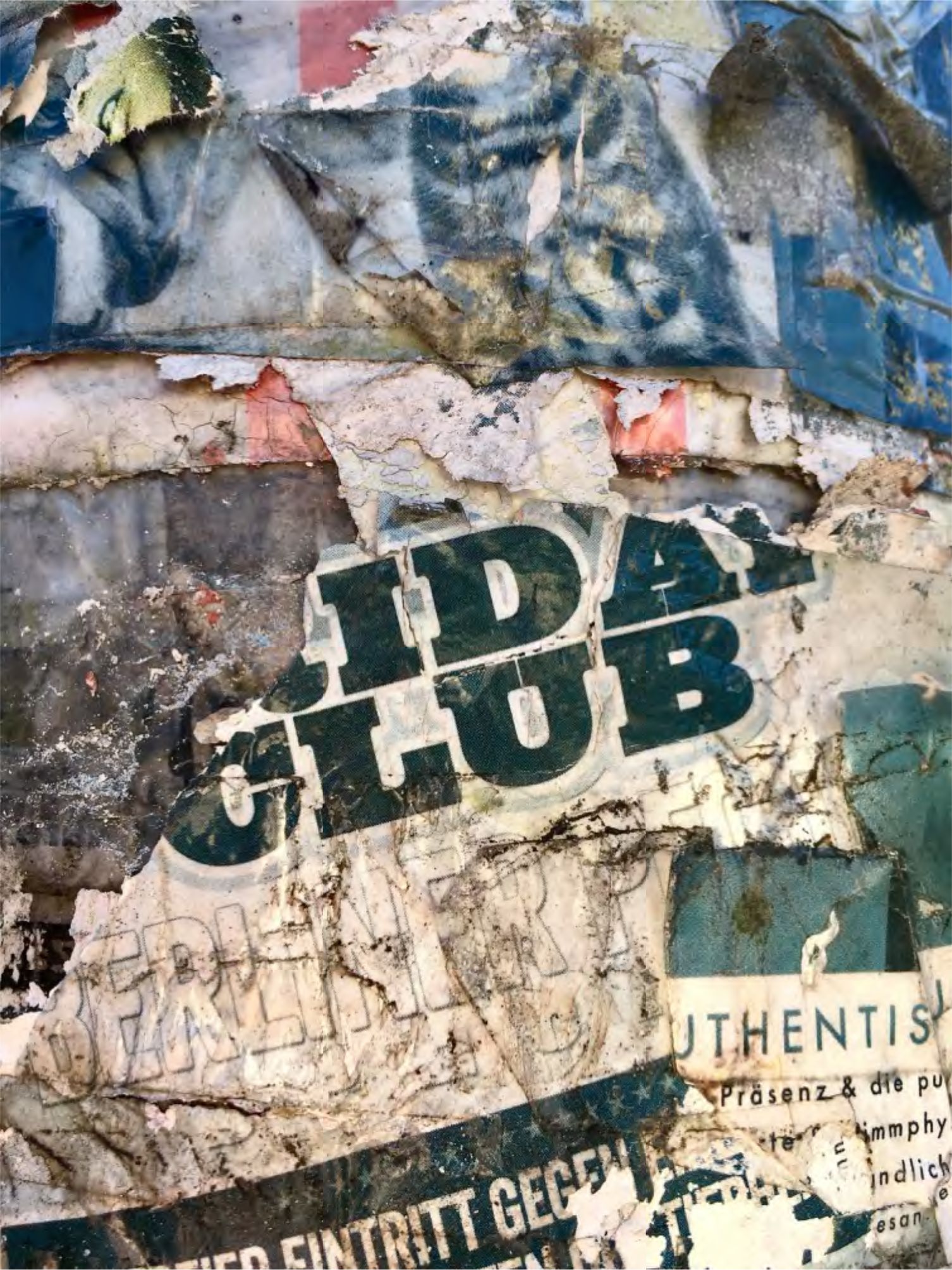

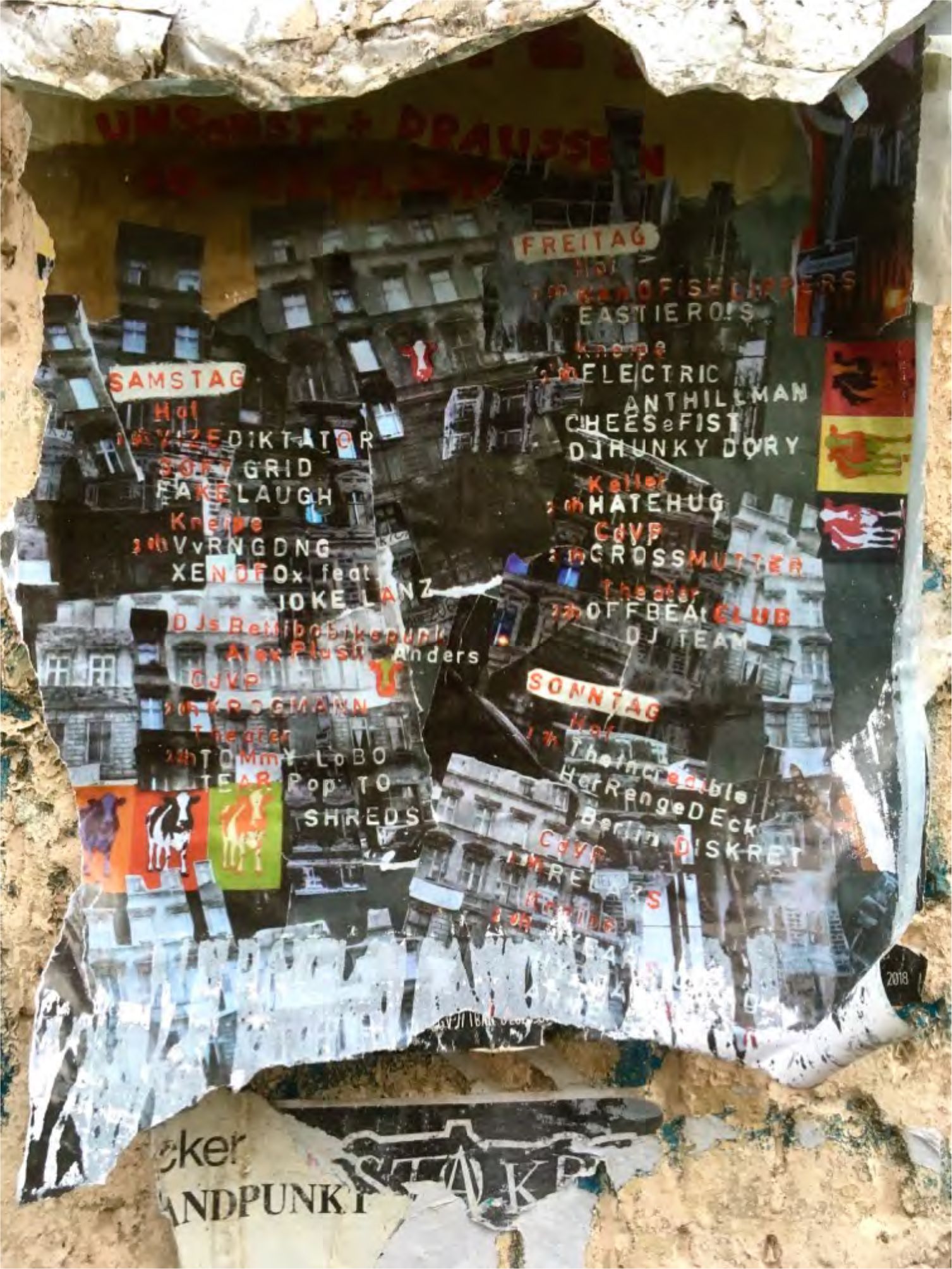

Every day I leave the house one, two, sometimes three times, but since I’m in public and avoid all means of transport and am without wheels, the terrain of my movement is manageable. From these new movements, something has emerged that I want to share: photos that I take with my smartphone when I go to the bakery or the supermarket, the drugstore, or around the square. They show posters and signs that overlap and decay. It looks so dead out in the “lively” districts of the capital, but now I feel the morbidity of this unwanted beauty is stronger; the poverty of intent that underlies it has been on my mind for a long time.

So, what I want to say is: art is created. Ambitions may fuel it, but ultimately something happens or not. Sometimes it’s casual. We cannot force that. It happens repeatedly when we have the impulses that “I think this is worth noting.” If poets, for example, no longer insist that poems are needed; if journalists, for example, think that that the public already has all the information they need, then we must be open to what is timely, what the moment brings.

Those who create art most of all, especially in the medium- and long-term, will be threatened by the aftermath of the crisis and must see that art is not a trade. Everyone is an artist, says Beuys. We nourish our ability, or let it atrophy, and excessive professionalism can be a way to gradually kill ability. So here are photos I took with my phone in the first few weeks in which Corona changed our lives. The first was taken in Ludwigshafen-Maudach, the others in Berlin-Friedrichshain.

Berlin, March 30, 2020

Dieter M. Gräf is the author of six books of poems, including Tousled Beauty (2005), Tussi Research (2007), and most recently, Falsches Rot (2018). He has participated in several exhibitions that pair texts and images: at the Literature Museum of Modern Art in Marbach am Neckar; the Literary Colloquium Berlin; and the Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Beijing, among others.