MICHAEL CARROLL AND BRIAN ALESSANDRO are intensely creative, opinionated, and politically engaged writers. They are also extremely social creatures. We knew they were working together closely, collaborating on a forthcoming graphic novel, among their other projects. We wanted to see how they were coping at the beginning of the pandemic, and to hear their point of view on it. Turtle Point asked them to talk about what their lives were like during the first weeks of quarantine.

Michael Carroll: I was cooking for a dinner party scene that we were shooting for my friend Brian Alessandro’s satiric film, A Saintly Madness, about a week before New Yorkers began taking the novel coronavirus seriously. There were some dozen people on set, including the mostly cameo players like Colm Toibin, my husband Ed [Edmund White], Rick Whitaker, and our writer friend Xan Price, each playing the kind of generally homosexual swellhead intellectual Brian loves to lampoon, plus a professional actor, Adam Griffith, the star of Brian’s first film, Afghan Hound. It was an evening of reshoots and laughter, and I don’t think anyone mentioned the possibility of a plague about to take New York by storm. But that was exactly what would begin to happen in a week or so. That evening was the last time before the subsequent long quarantining that I’ve seen most of my friends, including Brian.

MC: For as long as I’ve known you, you’ve been too restless with your various projects and making a living to settle comfortably into something like self-isolation. And yet someone as disciplined as you was precisely the sort of artistic temperament for whom this kind of thing was made. How’ve you been keeping yourself since the last time I saw you and the international news went bonkers?

BA: For better or worse, I throw myself into work. Especially creative work. There’s also my 40-hour-a-week day job, which has always been 100% remote, anyway, serving a company that provides support coordination for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. I’m their QEC—quality enhancement coordinator. I’m also still writing interviews for Interview Magazine (most recently the profile of drag queen/city council nominee Marti Gould Cummings), and books reviews for Newsday. I’m also exercising every day, bingeing on movies and TV shows, working on my film A Saintly Madness, and playing with my new puppy, Zelda May Rubinstein, named after the Poltergeist star and AIDs activist from the ’80s. I also talk to my mom and sister every day via FaceTime. Weirdly, I’ve never been so busy and productive.

MC: As I type this, my husband is Skyping with his trainer. He hasn’t been out of the apartment in something like twenty-four days. How are you physically dealing with isolation? What are you doing for exercise? Any unexpected benefits?

BA: I’m doing yoga, mostly. I’m also running along a deserted path near my mother-in-law’s home in New Jersey, which is where we’re hunkering down. I’m used to lifting weights at the gym, but I find these new routines to be pretty effective, and particularly calming.

MC: You’re known among my friends as the most disciplined and productive worker since Balzac, maybe even Daniel Defoe. Shakespeare famously wrote under the pressure of several plague bouts. Any new ideas coming out of quarantine?

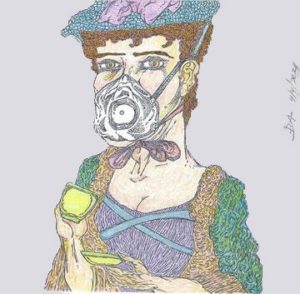

BA: I’ve completed a new illustration inspired directly by the pandemic. It’s called “Unaffected Classes” and it’s meant to be satiric. It suggests that this illness will mostly vanquish the most vulnerable among us, especially the poor—though, of course, viruses don’t discriminate. As I respond to this question, I see on the news that Boris Johnson is now in the ICU. I’m also working on the screenplay for A Saintly Madness, which Dennis Leroy Kangalee will be writing. As you know, I just directed a demo version, and am now slated to direct the feature this October. It, of course, stars you, Dennis Leroy Kangalee, Adam Griffith, and Tricia Vessey, the great actress from Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog and Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day. And we have cameos from Colm Toibin and Edmund White, too! As for the short film, I was lucky to be able to get the hard drive to my editor, and emailed files to my sound mixer and composer, so we can continue to complete it remotely. Thank god for this technology!

MC: Any shifts in artistic or aesthetic perspective coming out of this?

BA: I think so. The virus has found its way thematically into the screenplay. All of my stories have dealt with a social context (the big context) and then the larger context of the universe or nature or mortality, and I think COVID-19 is an example of that—the bigger context, the unseen, ignored threat. Climate change is another example. My work always plays with these hovering mega-dangers that we arrogantly ignore at our own peril. I like to write about hubris, privilege, and delusions of grandeur, and the Grecian consequences such apathy engenders.

MC: What do you do to wind down, and is even that difficult?

BA: I watch a lot of TV! Tiger King, Ozark, Schitt’s Creek, and Drag Race, but also great films. Recently, I saw Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendour from Thailand. Also, The Ballad of Narayama and Vengeance Is Mine by Shohei Imamura. And Zama by Lucretia Martel. I also find cooking meditative. And exercise saves! I have to tax my body every day as a sort of therapy, a tranquilizer. Oh, and Zelda is a great diversion! She soothes me. My husband and I are spoiling her already.

MC: Are you more connected with people in your family and social circle than usual? Is there a qualitative or textural change in these conversations?

BA: Yeah, well, I FaceTime now a lot more. Conversations are longer and less hurried. I am more patient and more inquisitive. There’s more gratitude on both ends, and I suppose that’s a silver lining. Being forced to assess what we have and what might be taken from us. Appreciating everything we’ve probably taken for granted, including going out, seeing people, physically connecting with others. Our health, of course. It reminds me a bit of the three months I spent in India in 2008, where I lived with friends and spent a good deal of time hiking and meditating and releasing creature comforts. And the twelve-day Vipassana silent meditation retreat I went on in Western Massachusetts in 2013 comes to mind. I surrendered my phone, books, laptop, and meditated for ten hours a day, woke up every morning at 4am to a gong, fasted most of the day, and avoided uttering a single word for the duration of the time there. It was the most difficult thing I’d ever done, but it’s prepared me for this unnerving, surreal period.

MC: What did you do to get ready to go into hiding?

BA: My husband, Tommy, and I decided where we were going to ride it out and left our apartment in Chinatown. I have mixed feelings about leaving. Guilt, mostly. We also stocked up on food. Psychologically, I felt ready. I love to socialize and go out and am prone to cabin fever, but I was able to slip into this mode without too much effort. I’m more worried about my loved ones. Everyone I care about the most lives in New York.

MC: What are your greatest hopes or fears, in your brightest and alternately darkest moments, while you’ve been alone or semi-alone?

BA: My greatest fear is that people will be left with permanent psychological scars from this and become cruel to each other out of a collective survivalist panic. Or worse, that we forget about it and become cavalier in our behavior. My greatest hope is that this horror show wakes everyone up. Helps us see ourselves and each other more clearly. Helps us prioritize. Helps us maybe care less about the shallow, superficial things. Helps us value great art and nature and friends.

MC: We’ve seen a pretty steep drop in traditional artistic and cultural manifestation. No new big novels announced, theaters are closed, museums and musical venues, anything involving a crowd and going outside of the home. Thoughts, observations?

BA: All artistic industries returned to business as usual after the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic killed 50 million people around the world. Art will bounce back. Hopefully, there will be innovations along the way—maybe smaller films that take place in filmmaker’s homes. I imagine that this period of quarantine will produce more introspective work, deeper work. I also suspect we’ll see the predictable spate of viral pandemic disaster films like Contagion or Outbreak, though we don’t need more of that in our culture. Let the influence be thematic, symbolic, not literal. That’s boring.

MC: As a culture, what are we poised to gain or to lose when at least the first phase of the virus’s effects and our attempts to contain and reverse them is through?

BA: Going back to my previous answer, I think this virus won’t change anything, but rather, will reveal and amplify what’s always been there—selfishness, greed, indifference, but also altruism, compassion, and community. Bad times make bad people worse and good people better. We’re seeing it already, and I believe that the effects will linger. It will take a long, long time for people to feel comfortable at the gym or movie theater or sports events again. I also think that the paranoia will persist for years. People will be ostracized or beaten if they exhibit symptoms of any illness in public for a while. Finally, I am disgusted by the bigotry against Asian Americans. It happened with Middle Eastern people after 9/11 and it’s happening again with this. It’s unacceptable and it must be condemned often and loudly.

MC: What artist or writer or musician or combination of any of these have meant the most to you during all this? Any takeaways?

BA: I’ve been listening to Counting Crows, Bjork, and The Smiths. They’re reliable. They always mitigate. I also read Carmen Maria Machado’s imaginative and moving memoir In the Dream House, and What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell, in which he does an impressive job of capturing elliptical sensations and the dark complexities of gay relationships. And then all those wonderful TV shows and films, both old and new, international and American, derivative and deadly serious. My moods shift. Sometimes I want to be distracted. Other times I want to look life in its beautiful, ugly face.

MC: What are your thoughts on the Black Lives Matter demonstrations? Did you see this coming?

BA: Racism is a collective delusion shared by deranged people with superiority complexes and sociopathic impulses. These people have benefited from mass historic system failures and mass moral system failures. They lack empathy and wisdom and humanity. We white people, with our systemic privileges, have an ethical responsibility to police our own and educate and correct bad behaviors.

MICHAEL CARROLL is the author of Stella Maris: And Other Key West Stories. His debut story collection, Little Reef, won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction and the Publishing Triangle Award. Originally from Jacksonville, Florida, he is married to writer Edmund White and lives in New York.

BRIAN ALESSANDRO is a filmmaker, novelist, and illustrator, with a background in psychology, which he has taught at the college level. His first novel, The Unmentionable Mann, was published in 2015 by Cairn Press. His first feature film, Afghan Hound, was screened at Left Forum and has streamed on Amazon and Netflix. He writes for Newsday and Interview Magazine, and is the founding editor of the journal The New Engagement.