by Jarid Manos

MOMENTS IN OPEN COUNTRY CLASH into human trauma crosswise and leave you different—if only for a while.

On a hot Sunday afternoon in July, I finally made it back to the Everglades. My Specialized mountain bike scissored along the 15-mile loop trail. Again the scale of such pristine prairie struck me. Who would’ve thought Miami would lead the country in preserving prairie, a landscape typically emblematic of the American West? Just west of town, open country surged with life: birds, wind, grass, water, fish, heart, bloodstream, breath, and three thunderstorms lining up on the western horizon. No motors or industrial noises at all.

The sun, a yellow fireball, burned high in the blue sky. I rode, sweated, and listened. An unseen alligator bellowed. Leopard backs of Florida garfish broke through surfaces of sun-spiked and white-cloud-reflecting freshwater sloughs. Red-eared slider turtles poked their lips into the air to breathe as if their necks were drinking straws.

The Marjorie Stoneman Douglas wilderness prairie of Everglades National Park is almost a million acres, something unimaginable out West. The first time I rode my bike here the virgin sawgrass prairie reached into my chest and pulled my heart out as it swept to the horizon: clean, untouched, primeval.

Earlier in life I traveled repeatedly into the backcountry of America’s “iconic” Great Plains, seeking refuge in Open Country from prostitution, drug dealing, and myself. I had this inflamed idea that I could escape unresolved personal traumas and wretchedness, purify my soul in the space and sky of wild grassland. But as I slipped under the barbed wire fences, as my shoes pressed into the dry dirt that cracked between patches of buffalo grass and blue grama, I became unnerved, then angry.

Out West, as I experienced it, America’s grasslands were appropriated by men wielding a culture of violence and domination not changed since the Indian Wars and buffalo slaughter of the 1870s. Instead of grass wilderness I found barbed wires stretching to the horizon, cattle overgrazing, prairie dog killing contests, aerial gunning of animals like coyotes from airplanes and helicopters, rampant poisons, snares, traps, and wrecked creeks and springs. The backcountry danger could easily at any moment extend to humans, particularly of browner shades, from some armed ranchers and cops.

My anger overtook me. Young, ragged, and militant, I fought back, hiding out, cutting the hated bristling wire fences, defending prairie dogs, and other acts, until I collapsed traumatized from that, too, a 1990s speck subverted on a barricaded open land under an immense and releasing sky.

I never found the refuge I sought, but eventually I did manage to stabilize, heal enough, and grow to move on, including starting a non-profit.

Time hurtles; wounds close; scars fade. I used the optimism of hard work — service to others and our Earth—as a shield, and largely avoided personal life situations that could scathe me again.

And I almost made it. Damn. But a few years ago I met the love of my life and it’s crazy—it was actually love at first sight. Yeah, it really exists. The experience was like a blast furnace, both good and bad. When the relationship had to end, I didn’t even know pain like that existed. And I’d had my share.

The abandoned fire watchtower at the midpoint of the Everglades loop trail rises several stories in a concrete spiral; it is very much an alien outpost left behind in this grass wilderness.

Up on the concrete platform, again my chest caught. The perfect green and yellow prairie unfolding to the horizon was my hallucination in real life, what I had wanted all those years in West Texas and Kansas and eastern New Mexico and eastern Colorado. You’d have a hard time walking most of it, too wet, but it was here, and it was wild and untouched.

To the west the hot July blue sky dimmed. The three single thunderstorms were moving closer and it seemed as if they had come straight across the Gulf from Texas, my state, my once-and-never Promised Land. I saw that it was nearly a thousand miles of wild Open Country, first sawgrass, then the tuna-blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico all the way to Texas. The prairie and the ocean are two halves of a whole. And Florida is just this narrow low-lying peninsula between Texas and Africa.

Out in Open Country, prairie storms boil into the troposphere like atomic bomb mushroom clouds. They are the cleanest, most thrilling reverse expression of that power. The storms grumbled and boomed, communicating attack plans with each other.

On the abandoned watchtower, the still-quiet wind blew through the metal helix staircase rising through its center. At certain angles I realized it sounded faintly like my ex playing his red clarinet, as if far away in the distance, baseball cap tilted up, blowing into the reed instrument, eyelashes lowered, then grinning. I sat on the concrete floor for an hour.

On my way back the storms arrived and merged, first rushing me with a swirling air-and-debris bomb of 15-degree cooler air, then furious sheets of sideways-slapping rain, dousing the embers in my head and chest. I scrambled into one of the little hardwood hammock islands—the only place of trees—where the Seminoles and Miccosukees used to live, gasping drops of water until it all passed.

In the clearing aftermath of the deluge, the red-orange-pink sunset dried out the air, and final shots of white-purple lightning crackled the underbelly of departing black clouds. Spears of rainbow struck the Earth, absolutely blazing their colors into new standing water. In a hundred years this will all likely be the sea floor, but for now it’s here, this river of grass, where fire and water meet.

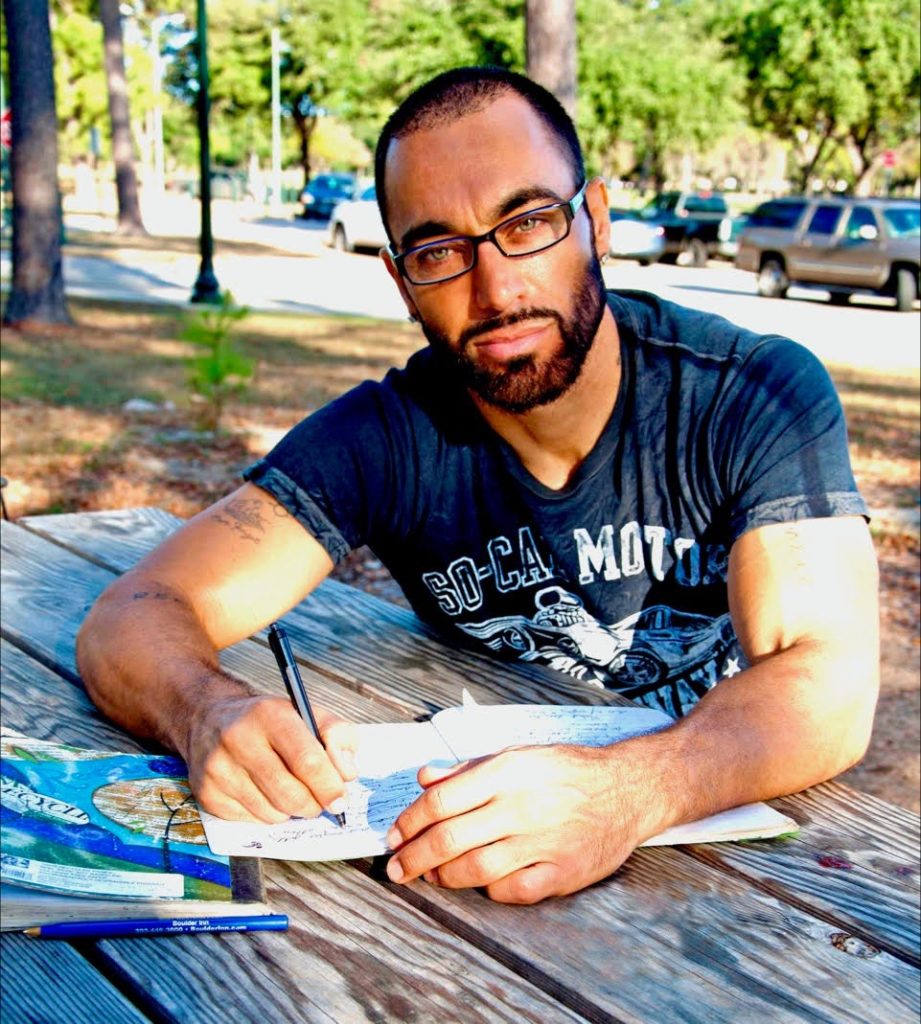

All photographs by the author.

Jarid Manos is author of Ghetto Plainsman, soon to be a feature film, the forthcoming short-story collection The Sun and the Water, and the novel Her Blue Watered Streets. He is also founder of the non-profit Great Plains Restoration Council. As a writer, activist, and vegan athlete, he has built his life’s work out of the realization that “the violence we do to the Earth mirrors the violence we do to each other and often accept into ourselves.” Follow him on Instagram: @jaridmanos.