by Herman Portocarero

1. BEYOND THE BARRIO of La Muñeca, leaving Havana heading toward San Antonio de los Baños, the city gradually turns rural. Or, to the inextricable mixture of textures at the edge of any large city, only more confusing in Havana’s case, because history has had such a dramatic break here. Where once a baron would build a mansion, a few decades later a Communist built a factory, or turned the mansion into a school, a clinic, a research center, or, always a favorite, a police station.

Cuba before the Revolution had a rich culture of eccentrics living in these lush areas just outside the city. The most notorious one built herself a castle where she kept an entire pseudo-royal court of dressed-up monkeys. La Finca de los Monos entered Havana urban legend, but it was entirely real. Then the Revolution did away with such aristocratic eccentricities.

Oscar Soriano’s story was not quite in the same league, but there were similarities. Oscar was the caretaker and yard man of a small palace hidden behind thick bamboo groves on the outskirts of La Lisa. The house was a large villa in a mixture of styles, a hybrid between a Venetian palazzo and a medieval Rhine castle. The property was owned by the Nuñez-Vegas family, and the head of the family had been an amateur beekeeper. After the family fled to Spain in 1962, they left behind a young cousin, Angelito, under Oscar’s guardianship so as not to lose claim to the house.

Angelito turned out to be autistic, and never finished grade school. Until the Revolution instated its brand of political correctness, Angelito was considered the village idiot and was treated as such. After the age of fifteen, he never passed beyond the outside gate of the property. Oscar had him help with the bees, and for some mysterious reason they would never sting him, even when he opened or fumigated a hive unprotected.

The last of the Nuñez-Vegases died penniless in Madrid in 1975. Letters and money had long ceased coming to the villa. Left completely to his own devices, Oscar little by little expanded the beekeeping operation to sustain himself and Angelito. He started by selling their honey, first to the neighbors, but gradually to a wider clientele, steadily growing through Havana’s lively grapevine culture, radio bemba or word-of-mouth.

His operation was too small at first to attract attention during the various waves of Cuba’s economic reform, ending with the total prohibition of any private production or commerce. Since he employed no workers except for the otherwise helpless boy, and purchased no supplies, he was technically not running an agricultural or industrial operation or anything else falling under the new laws.

Once in 1976, though, some overzealous paper pusher in the Ministerio de la Industria Alimentaria who was out for a promotion sent an inspector to the house. He entered the property with the usual air of importance, proud of the status conferred by his polyester guayabera and the fake Samsonite attaché case made in the USSR (an important symbol of authority, but almost never containing more than an extra pack of cigarettes). When, in the usual manner, he tried to interrogate the “unlicensed worker” and the offending economic operator, Angelito didn’t utter a word. Instead, he opened a beehive, and the bees—reading his peculiar mind, which was attuned to their own instincts—massively attacked the inspector, who fled the property. The following day the ministry sent a report to the local police station, but the cops were all getting free honey from Oscar and never followed up on the complaint.

Life at the villa carried on in this fashion for another forty years. The mansion gradually crumbled, and its use was reduced to the kitchen and two rooms on the ground floor. Oscar, in his eighties, shrank to skin and bones, but maintained an enviable state of health through a sparse diet, little rum, regular doses of royal jelly, long rides on his Chinese Flying Pigeon bicycle to deliver jars of honey far beyond his neighborhood, and sex once a month with a willing widow from the nearby hamlet.

Angelito went the opposite way, expanding to the size of a newborn elephant baby, but maintaining his innocent eyes and his diminutive “little angel” nickname. The only annoying habit he developed was to masturbate before any female visitor to the yard; luckily, there were not that many coming. He was by now technically the owner of the ruined mansion and grounds, but since he was recognized to be legally incompetent, Oscar handled any stray document that would come in requiring a signature.

2. Sergio, the youngest staff writer of the official daily Granma, was sent to the finca with the delicate mission of extracting a human-interest story without deviating from party lines. It made him nervous, but he set out valiantly.

The bus to La Lisa was crowded at first, but had almost emptied by the time it reached its final stop at the ragged outskirts of the barrio. Sergio got off and asked his way to the Finca de las Abejas. It was late May and the bees had done their work: the dark mango trees had bloomed profusely and were now pregnant with fruit. Kids from the scattered housing projects carried long bamboo poles equipped with the hooks of metal clothes hangers at the ends, to go after the ripe mangoes.

The housing schemes in these parts were low-rise units with verandas, colorful laundry drying in the breeze. Some enterprising neighbor had turned his cemented front yard into a proudly advertised car wash. Already looking for the competitive edge, the sign announced Se Fregan Carros Camiones y Tractores—We Do Cars, Trucks and Tractors. The only visible equipment was a new garden hose, but it was obviously treated with the respect of an investment.

In spite of fifty years of political correctness, the owner of the car wash, when asked for directions, still explained to Sergio the shortcut to El Castillo del Gordo Loco—The Crazy Fat Man’s Castle. Beyond the inhabited housing schemes, a vague zone of with the skeletons of buildings in rough gray concrete was either a work in progress or abandoned, difficult to tell. Creepers embraced the concrete, but that didn’t prove anything: microbrigadas building their own apartments sometimes took years to complete them, but they never gave up. The buildings served a purpose even as they were: lovers out for a bit of privacy had left graffiti commemorating their best moments on the walls.

Past these constructions, the asphalt road gradually ended and soon was just a dusty path nearing the dark bamboo jungle rustling and clicking in the breeze, shielding the ancient mansion. Two skeletal but still hopeful street dogs, never giving up on life either, continued to follow Sergio for a while. The gate through which he entered the property faced east, on the Venetian side of the mansion, leaving the medieval German side to the darker west. The path inside the gate was slippery with moss under the deep shadow of the bamboo groves.

The welcome Sergio received from the two characters inside was wary at first. Oscar still took his responsibilities as a yard keeper very seriously, and was busy cutting weeds against the impressive backdrop of the drooping house. Oscar’s sparse, angular body was dressed in baggy shorts and torn rubber boots, with the symbolic leftovers of a T-shirt framing his torso. This walking skeleton equipped with a sword looked menacing. To complete the impression, a broken shutter of the house was flapping in the wind, like the loose yardarm of a ghost ship, the entire house the color of a stranded wreck.

Oscar took Sergio, with his shiny leather shoes, at first for another inspector. Angelito stood by in mute understanding but in sharp readiness, in case bees had to be released against an invading enemy, but otherwise behaved himself, as the visitor was male.

When Sergio explained the purpose of his visit, Oscar apologized that he had no coffee to offer but that he could make herbal tea with honey. Sergio had his doubts about the grimy old man making him something to drink, but accepted as an ice-breaking courtesy. Oscar disappeared into the kitchen. Sergio, abandoned on the terrace, checking indiscreetly through broken windowpanes, saw vague objects that looked like an alchemist’s tools on a cluttered counter indoors. Oscar came back with two steaming cups. They sat down under a mango tree and talked, Sergio holding his little voice recorder.

“What drew you to beekeeping, compañero?”

“I had no other option to survive. We were abandoned here and I had to take care of Angelito.”

“The former owners of the property fled with their riches?”

“They were flat broke.”

“How do you see the bees?”

“They just do their thing.”

“You mean that they form their own societies? What did you learn from them?”

“They work hard for no pay.”

“Under strong leadership, right?”

“They have a queen, yes. A kind of monarchy.”

“But led by a female. That’s remarkable emancipation in the natural world, no?”

“They are slaves, asere. Working hard for the honey enjoyed by others.”

“They always stick to their duties.”

“What choice do they have? It’s all they know. They buzz a bit, but mostly they shut up—for if they sting, they die.”

“You know that bees are dying out in the rest of the world? That here in Cuba they are still safe?”

“We’re good at keeping everything going that’s long finished elsewhere. Like the almendrones and my bike. And myself,” he added.

“Our air is just better for them, less polluted.”

“Joven, have you ever been on a bicycle breathing in the exhaust fumes of an almendron? Maybe I’ve been living this long because by now I’m smoked meat.”

Sergio came to the most far-fetched part of his brief.

“Have you heard that great Cubans are modeled in beeswax in an important museum in the United States, en Nueva York ?”

The old man enthusiastically scratched his balls, somewhere deep in the wobbly area of his baggy shorts.

“I sell the stuff to chicks, for their legs and for their thing, you know. The yumas like ‘em smooth, but I myself….”

Sergio cringed, but on Oscar’s otherwise impassive face, the mental association brought out a decidedly subversive grin.

“If they make… personalities out of it, they should keep them in the shade. You don’t want important figures to melt.”

Sergio was alarmed, then realized no one else was within earshot and that the dangerous joke would not be reported. But shit—he still had it on tape! He’d better erase this part. … He resumed the interview on another of the suggested topics:

“The bees pollinate all over the place. You help the mango trees and the natural cycles. It looks like a rich season.”

“Mangoes? Kids steal some of them, and the rest go to rot. A nuisance more than anything else. Clouds of flies. Ants. And people in the city, they buy mango juice en cajita from abroad. I’m old but I see things when I ride out to make my deliveries …”

“How does that work?”

Oscar’s expression signaled that this was an exceptionally stupid question.

“I ride my bike. I mounted a wooden Hatuey beer crate on the rack in 1972 and it still holds. The Hatuey beer is long gone, but they made the best crates. I can fit twenty- four jars of honey in the crate.”

“How many buyers do you have?”

The old man had never forgotten the visit by the inspector, back in 1976, who had tried to turn him officially into a black market operator. His mistrust of Sergio came back.

“I have no buyers, only people who love the honey.”

“Who are they?”

Sergio himself felt these were foolish questions the moment he asked them. He was further losing the old man’s trust. Oscar’s eyes were constantly fixed on Sergio’s shiny shoes now.

“I have all the addresses in my head,” he said warily. “And names? I know them as La Gorda, El Angolano, China Flaca, La Reina, El Negro Prieto, La Mulatisima…”

Angelito, sensing the tension and reading his companion’s alarm at Sergio’s growing invasiveness, slowly walked towards the beehives on the backside of the house.

The journalist said hurriedly that he had enough material, thanked his host for the hospitality and quickly made for the gate. But Oscar, following his own well-trained instinct, told him to wait a minute, disappeared in the house and came back with a jar of honey carefully wrapped in a sheet of Granma newspaper. ‘I’m accepting a bribe’, went through Sergio’s immature professional brain, but he didn’t know how to refuse. Instead, his eyes stupidly read a fragment of the Granma article of the wrapper, a red headline about Venezuela. He said a vague thank you and made for the exit.

Back on the road, it occurred to him that he hadn’t even seen the beehives.

3. It took Sergio the best part of the week to come up with his human interest article for the Friday edition:

La Finca de las Abejas: Of Bees and Men

One of the many successful innovations in our national food policies is the expansion not just of suburban agriculture, but of apiculture on the very doorstep of our capital city. Compañero Oscar Soriano, living on the outskirts of the municipio of La Lisa, aided by his ward Angelitoa sturdy worker, in spite of his mental challenges—is a veteran of the art of beekeeping. He took up his demanding craft when the owners of the property emigrated after the Triumph of the Revolution and, with the selfishness of their doomed class, left him and Angelito to fend for themselves.

In his eighty-five years Oscar has absorbed much of the wisdom of the industrious inhabitants of his numerous hives. He admires their ceaseless work ethic and their structured society. ‘It’s not just about the honey they produce’, Oscar says proudly; ‘they also play a vital part in the natural cycles by pollinating the mango trees in these parts. We’ll have an exceptionally rich harvest this season.’ He’s well aware that the pollinating bees, outside our island, are threatened with outright extinction by the degrading of the environment by mindless capitalist industrialism.

Oscar generously shares the honey with his neighbors, and even rides out on his vintage bicycle to make deliveries in other barrios, to friends fondly evoked by their colorful nicknames.

On an unexpected note, showing that in spite of his rural background, he is aware of cultural riches as well, he adds: and the wax, which many people only think of as a by-product, serves a better purpose too. I have sent much of it to our national museum of wax effigies in Bayamo, where the likenesses of our national heroes molded in wax have nothing to envy in such museums in the United States, where even Fidel is portrayed, from what I hear.’

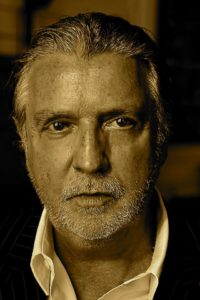

Herman Portocarero is a Belgian-born writer of Spanish and Portuguese descent. He is the author Havana Without Makeup: Inside the Soul of the City (Turtle Point Press, 2017) and has published more than twenty works of fiction and nonfiction in Europe. Between 1995 and 2017, he was ambassador in Havana for his native country and later for the European Union, and developed a deep professional and personal relationship with Cuba, Havana, and her people. “Silence of the Bees” is an excerpt from his collection Habanera/os: Tales from True Havana.